As we have

discussed before, we enjoy sports quite a bit. Given that nothing is more meaningful than anything else, we would generally prefer to watch a sporting event than (for example) a political debate. In part this is because most people recognize the absurdity of sports (i.e., while many people may

feel strongly about their team, few would put sports on their list of "important" things), but it is also because...well, we just enjoy it.

Now, at first blush this may seem at odds with the absurd, particularly since we have teams for which we "root" based purely on the area in which we spent our formative years. As Jerry Seinfeld so aptly put it, since the players on any given team are constantly changing, fans are essentially cheering for pieces of laundry. But far from being an impediment to enjoyment, we view this as an integral component of the "case" for sports, as it were. To wit, how can you not recognize the absurdity of the situation when you are suddenly rooting

against the same person you cheered for yesterday...simply because he is wearing a different shirt?

What got us thinking about this was a sporting event we watched the other day (with Inigo, as it happens), in which "our" team (not Inigo's) not only lost, but lost in excruciating fashion (i.e., they looked sure to win, but lost at the last possible moment). Further, the "consequences" of the game will almost surely be significant, with our team likely to be placed in a less advantageous position should they make the playoffs. It was, in short, a bad loss.

Now, there were a couple of things about this we found interesting. To begin with, we found it difficult to place this event in proper context--despite our strong belief in the absurd, we nevertheless found ourselves reliving the loss in our head, wishing the game had ended differently, and thinking of various "bad" outcomes that could ultimately ensue for the team. This is, to be honest, a bit embarrassing--here we are preaching the virtues of living the absurd life, and we are obsessing over a football game?!?

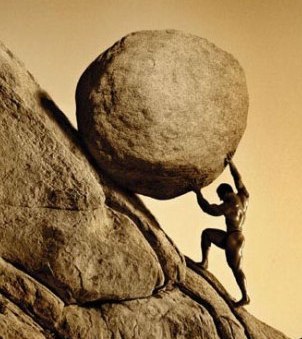

On the other hand, this very reaction provided us with an invaluable "teachable" moment for ourselves. Put simply, we began to investigate

why we found this upsetting, and to see if there were broader lessons to be learned. More specifically, we wanted to get to the "first principle," i.e., the underlying issue that caused us to lose perspective...

even when we knew it was ridiculous! As we see it, our reaction was an example of the double-edged sword of abstraction.

As Douglas Hofstadter explored in his terrific book "

I Am a Strange Loop," humans (and all living beings, for that matter) by necessity live in a world of abstraction. In other words, it is far more useful to "see" a steak on one's plate (for example) than a seething mass of particles, despite the fact that both are accurate descriptions of the object in question. Further, there are many different levels of abstraction.

For example, at a basic level a sporting event is simply a group of people running around with a ball; it is only our "knowledge" (of the rules of the game, win-loss records of the teams, etc.) that gives this motion significance. Our "concern" over our team's ultimate prospects for the rest of the season, meanwhile, take the abstraction up another level. Indeed, at the top of the chain is the question: why will we feel good if they win the championship? We have no financial stake in the outcome; we do not know these people; and, as noted, our feelings for the "team" are independent of individuals (i.e., the team itself is yet another abstraction).

Indeed, the only tangible benefit to their winning seems to be our ability to share this joy with other fans...and lord it over those who root for different teams (!) This is circular logic in the extreme - said a different way, we hope our team will win so we can celebrate with others who have the same hope. What kind of madness be this?

Going in the other direction, the individuals who comprise the "team" are also abstractions (if you believe, as we do, that there is no self) - simply random collections of matter

complex enough to become self-referential. Further, we were not physically at the game, but rather watched it on television at a bar.

Thus, one could logically argue

either that the cause of our angst was a tough loss that really damaged our team's chances of winning the championship...or a collection of flickering lights on a screen. Both are correct; neither is a "better" explanation than the other.

And this is where abstraction becomes a double-edged sword. For while it is certainly true that the individual who "sees" the steak is more likely to survive and pass on his genes, this seems less likely to be true of those who follow sports teams.

Said a different way, while abstraction is crucial to our survival,

it is also the source of most (perhaps all) of our worries and regrets. Looking back, we also realized that by building up the game prior to its occurrence (talking to friends, etc) we had enhanced the abstraction in our own mind. In a very real sense, we believed that the game mattered--that we would be "better off" if our team won, and worse off if they lost. The sheer idiocy of this position was swamped by our genetic nature to see things as abstractions

if we are not sufficiently careful.

Indeed, the spread of technology means many people live much of their lives in a state of near-constant abstraction. Communications are via email and telephone, while most "knowledge" is gained through reading (writing being an abstraction of others' thoughts). That this would give many people a false sense of superiority (for lack of a better term) is not surprising, and explains much of what passes for "wisdom" these days.

It is, for example, much easier to offer a "solution" to a broad social problem (e.g., the US government should run the health care system--think for a minute about how many abstractions are embedded in that one statement) than to ease your neighbor's suffering (or your own!).

Well, we've rambled enough for one day, but let us close with this thought - while we were initially upset that our team lost, the fact that they did gave us a wonderful opportunity for self-reflection, and (we believe) gave us yet another fresh perspective on the absurd. It puts us in mind of one of our favorite Homer Simpson quotes: "Donuts...is there anything they can't do?"

Until next time...