We watched The Family Man again the other day. As we have noted, it is among our favorite films due to its wonderful (albeit almost certainly unintentional) template for living the absurd life. We return to it again here for two reasons. First, this issue is central to the concept we continue to explore in this blog--namely, how to live a content life in a decidedly non-absurd world, surrounded by non-absurd people. And second, as with most films, we pick up new things each time we watch it.

To recap the movie (from our prior post):

"Nicolas Cage plays a high-flying Wall Street exec (Jack Campbell), living what can only be described as the ultimate bachelor life--high-powered job in NYC, expensive car, beautiful women at his beck and call, etc. However, after a chance encounter with Don Cheadle (who plays something of a guardian angel), Campbell wakes up the next morning to find himself married (to his old girlfriend Tea Leoni) with two children, living in the NJ suburbs and working as a tire salesman. Basically, it is an alternate universe where Campbell made different decisions and thus his life turned out differently."

What we found interesting this time (and did not consider in our prior post) is that from Campbell's perspective, the people surrounding him in his "alternate life" do not really exist. Thus, he spends zero time worrying about what they are thinking, trying not to offend them, etc--to him, they are purely superficial characters in a very realistic play, perhaps akin to a lucid dream. In short, he is playing the role of someone who physically resembles "himself" in every way, but has a different background and thus different desires and emotions.

The point, of course, is that once one accepts the absurd, it is possible to play whatever role one chooses. Any of us is free, at any moment, to shed the personal experiences and history in which we invest so much meaning, and live each moment anew. Rich or poor, old or young, it makes no difference. It does not matter if one has children or not, lives alone or with family, is healthy or sick--none of it matters.

As Krishnamurti so eloquently put it:

“You cannot live without dying. You cannot live if you don't die psychologically every minute. This is not an intellectual paradox. To live completely, wholly, every day as if it were a new loveliness, there must be a dying to everything of yesterday, otherwise you live mechanically, and a mechanical mind can never know what love is or what freedom is. ...To die is to have a mind that is completely empty of itself, empty of all its daily longings, pleasures and agonies. Death is a renewal, a mutation, in which thought does not function at all because thought is old. When there is death there is something totally new. Freedom from the known is death, and then you are living.”

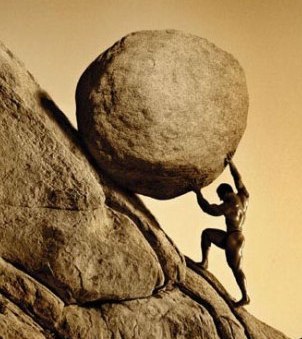

Who is the "real" Jack Campbell? What about the "real" Nicolas Cage? (Or the "real" you?) Such questions are not only unanswerable, but the more one attempts to answer them, the closer one comes to realizing their fundamental meaninglessness. Whether one chooses to accept it or not, the "person" we each believe ourselves to be is nothing more than a role we are free to change at any moment. By mindlessly playing this role day after day, we subject ourselves to the tyranny of the past, unwittingly (and unnecessarily) enslaving ourselves in the shackles of identity.